What Are the Benefits of Earned Value Management for Government Agencies, and What Does the Process Look Like?

Earned Value (EV) is an essential part of doing business with the United States government—especially if you’re managing large-scale projects for the Departments of Defense and Energy (DOD and DOE). But what is the purpose behind EV requirements for government projects, and what does the EV process look like?

In the following sections, we answer these questions and provide a foundation for understanding EV with (1) a brief review of the benefits of Earned Value Management, (2) an exploration of when government agencies need EV, and (3) how the EV process typically unfolds.

What Are the Benefits of Earned Value Management?

The primary benefits of EV include the following:

- Help understand how the program is progressing.

- Determine if we are executing per the project baseline plan.

- Track whether the project will finish on time and within budget.

- Provide early alerts to help proactively mitigate technical, cost, and schedule issues and risks.

When Do Government Agencies Need EV?

Most government agencies and projects need to leverage EVM to improve project delivery. Also, many government contracts require an EVMS for oversight purposes. As for measuring the appropriateness of using EV in different circumstances, as each of the following risk factors increases, the need for EVM increases:

- Technical risk. The less proven the technology, the higher the risk.

- Schedule risk. The longer the project – and the more likely it can delay – the higher the risk.

- Cost risk. The greater the project cost – and the more it can grow – the higher the risk.

Download our Earned Value Management guide here!

Download our Earned Value Management guide here!

What Does the EV Process Look Like?

To provide a better picture for what the EV process looks like, this section provides an overview of the main steps that the EV process requires:

STEP 1: DOES THE CONTRACT STATEMENT OF WORK (SOW) “FLOW DOWN” EV?

The 1st Tier of EV flow down: The Government flows down EVMS to the Prime Contractor who flows down to Major Subcontractors who flow down to key suppliers (as needed). Look for these contract clauses to confirm if an EVMS is required for a contract:

- DOD and DOE:

- Part 7 of Office of Management and Budget (OMB) Circular A-11.

- DOD: Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement (DFARS) Clauses:

- DFARS 252.234-7001: Specifies requirements and compliance with the 32 EVMS Guidelines contained in the Electronic Industries Alliance EIA-748.

- DFARS 252.234-7002: Defines EVM reporting requirements.

- DOE: Federal Regulations and Policies specify when EVMS is — or is not — required for federal projects (which includes DOE programs):

- FAR 52.234-4, FAR subpart, 34.2.

- DOE Order: DOE O 413.3B – Program and Project Management for the Acquisition of Capital Assets.

The 2nd Tier of EV Flow Down: Contractual EV Reporting: Look for Contract – or Subcontract – Data Requirements List (CDRL or SDRL) and their Data Item Descriptions (DIDs). These provide instructions for completing each report, including file formats, frequency, thresholds, and even specific data fields. The regular monthly EVM reports include, but are not limited to:

- DOD (IPMDAR replaced the IPMR):

- Integrated Program Management Data and Analysis Report (IPMDAR).

- DOE (Some legacy DOD programs also use the IPMR):

- Integrated Program Management Report (IPMR).

- DOD and DOE:

- CFSR (DI-MGMT-81468A)

- Contract Funds Status Report (CFSR).

STEP 2: WHICH CONTRACT TYPES WARRANT EV?

Absent an EV requirement, which project or contract types warrant EV? We explore this by starting with the government or stakeholder perspective:

Fixed-Price Contracts

“Fixed” implies less risk to the government with the risks and rewards falling more on the contractor. These fall into three categories: 1) a firm – set or fixed – price for the project scope; 2) an award fee; and 3) an incentive fee. Incentive fees tend to be based on objective formulas and criteria while award fees tend to be more subjective and the government bears less risk. As illustrated below, the risk to the government is highest with a Fixed Price Incentive Fee:

Firm Fixed-Price (FFP) < Fixed-Price Award Fee (FPAF) < Fixed-Price Incentive Fee (FPIF)

Flexibly-Priced Contracts:

“Flexibly” applies to Cost-Plus (cost-reimbursable) contracts. Since the government bears the costs – even with large overruns – these are great candidates for full-scale EVM. The risk to the government is big, but negotiating an incentive or award fee for better performance is less risky than a flat, fixed fee on top of potential cost growth. Though not a hard rule, the risk to the government is highest with Cost Plus Fixed Fee, as illustrated below:

Cost Plus Incentive Fee (CPIF) < Cost Plus Award Fee (CPAF) < Cost Plus Fixed Fee (CPFF)

Indefinite Delivery / Indefinite Quantity (IDIQ) Contracts:

These have task orders, but – as the name states – the delivery schedule and quantity can change (grow or shrink). The customer is essentially setting up a contract vehicle for contractors to provide effort as and when needed. These can be very large contract values and can last years. The rule of thumb is if the task orders align with the characteristics described in this chapter, then EVM may apply. The more discrete, the higher the aggregate value, and the riskier the work, the greater the reason to apply EV.

STEP 3: WHICH PROJECT TYPES WARRANT EV?

Development vs Production Contracts:

Development projects are riskier than production contracts. Development involves design, development, and testing of new or improved prototypes and systems. Research and Development (R&D), Information Technology, and major capital projects are also considered development. Production projects range from low rate to full rate. As illustrated below, the risk to the government is highest with Development project types:

Full-Rate Production (FRP) < Low Rate Initial Production (LRIP) < Development

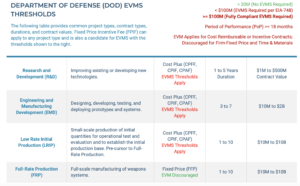

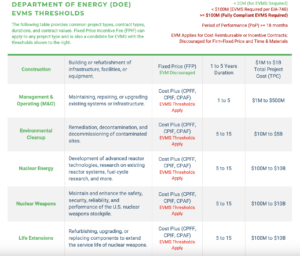

Based on Steps 1 and 2, we know when the contract flows down EV, but which project types are good candidates for EV? Below, depicts DOD and DOE project types, contract types, and when EVM applies. Typical project durations and contract values provided below may vary, of course. Note that the government can elect to flow down EV based on the project’s risk regardless of contract or project types, durations, and values. This is rare, but possible.

In DOE’s PM framework, key decision points in the capital asset project lifecycle are called Critical Decision (CD) milestones.

- CD-0: Approve Mission Need. After CD-0 factor EVMS data/use plus contract clauses into the acquisition strategy plan.

- CD-1: Approve Alternative Selection and Cost Range. Between CD-1 and CD-2 use or start implementing the EVMS for the initial Performance Measurement Baseline (PMB). EVMS surveillance for a compliant EVMS between CD-1 through CD-4.

- CD-2: Approve Performance Baseline. EVMS should ideally be implemented before CD-2 as it helps project teams define the scope, schedule, and cost targets in the Performance Baseline (PB) to improve project performance and outcomes.

- CD-3: Approve Start of Construction or Execution. Certify the EVMS prior to CD-3 (or combined CD-2 and CD-3).

- CD-4: Approve the Start of Operations or Project Closeout. End of EVMS reporting.

STEP 4: WHICH PROJECT TYPES DO NOT WARRANT EV?

EVM aims to avoid unpleasant technical, schedule, and cost surprises. We want to know if the technical scope is on track and whether we are going to delay scheduled delivery or overrun the cost. Thus, the more “boxed” a project — the less we need EV to manage that work. And when the time-box is less than 12 to 18 months, then that tips the scale to forgo full-scale EV.

- Scope-Boxed. The effort is either easily defined and/or it can flex such that the scope is highly unlikely to expand. Example:

- Level of Effort (LOE): The project has scope targets, but will never be late. It still has a specified cost and time and is useful for as-required support or services.

- Time-Boxed. Relatively short duration and unlikely to grow beyond the contracted period of performance (PoP). Example:

- Short Duration Projects: If the project is time-boxed to complete within 12 months (some say 18 months), then the benefit of full EV starts to outweigh the extra work of EVM. Consider using a scalable EV approach based on the project risks.

- Cost-Boxed. The effort with a maximum cost target that cannot be exceeded. Example:

- Time & Materials (T&M) and/or Not-to-Exceed (NTE): This can be an engineering or other development work with a “best effort” caveat within the cost limit.

STEP 5: CAN WE EVER WAIVE EV?

In rare circumstances, a project stakeholder can apply for a waiver of the EVMS requirement. Ironically, to require EV for Firm-Fixed Price (FFP) contracts, there’s a procedure in DFARS PGI 234.201 for obtaining a waiver before applying EVM.

Whether you’re a DOD or DOE agency or a contractor, navigating an EVM project doesn’t have to be stressful or intimidating. Download our free guide today! to demystify the process and provide the insights you need to achieve the outcome everyone in your organization expects.

Subscribe to our Newsletter: